The Absolute Necessity of Goals

The Biology of Goals

There is a hormonal system within the human brain that governs the release of Dopamine in response to a person’s perceived movement in the context of a goal. The release of the hormone Dopamine is associated with the experience of positive emotion, while its cessation is equated with the lack of positive emotion and the experience of negative emotion in more severe cases. In short, when you move closer to a goal you feel positive emotion and when you move further from a goal, you feel negative emotion. This Dopaminergic system also has an anticipatory element to it.When Pavlov's dog hears a bell, its mouth begins to water in expectation of a meal because one has historically followed the sound of the bell. My dog, Sheba, gets excited the very moment I touch a certain pair of shoes because she knows we’re about to go running. When you experience or expect positive emotion, the pathways in the brain that were used to acquire that feeling are also reinforced. In a literal sense, the electrical resistances of the circuits activated in pursuit of the goal are lowered. Functionally, less effort is required to send a pulse of electricity across neurons that are frequently used due to the lowered resistance. Mentally, things get easier if we keep doing them.

This aspect of reinforcement necessitates caution as there is potential to repeatedly engage in behaviors that immediately result in the experience of positive emotion with increasingly negative outcomes. People manifesting extreme addictive behaviors are known to take progressively more drastic measures to sate their addictive tendencies. An isolated rat for example, will choose cocaine over food and water until its untimely death. In most cases, the goal of experiencing the positive emotion associated with the object of the addiction has grown to outweigh all other goals currently possessed. On the biological level, goals are incredibly constructive or incredibly destructive.

The Notebook, It's Power

Studies(Here’s one) have shown that people who write a plan the night prior are possessed by lower levels of anxiety for that night, at the minimum. Napoleon Hill, Earl Nightingale, and a host of other self-help authors make it clear that physically writing down goals is critical to success. Extending on this position, in order to succeed or at least not fail in the most miserable way possible, an individual must compose a group of goals into a plan. "Failure to plan is planning to fail" goes the age-old adage attributed to Benjamin Franklin.

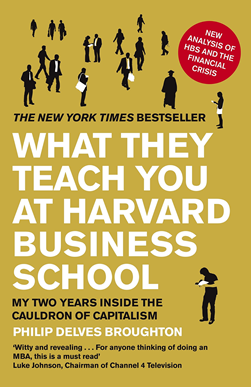

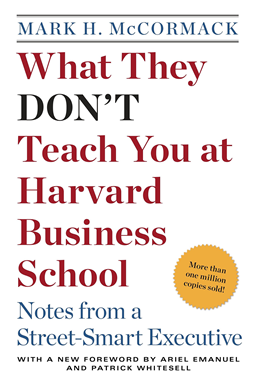

Behold! The sum of all knowledge:

The book 'What They Don't Teach You at Harvard Business School' contains an anecdote about graduates from Harvard's 1979 MBA program. When surveyed, 84% of the graduates responded that they had no specific goals. 13% said that they had goals but that they were not written down. Only 3% of the graduates had written out their goals and thereby formulated a clear and definite plan for their accomplishment. A secondary survey of the graduates after 10 years revealed that the 13% who had goals that were not written down made twice as much the 84% with no specific goals. The 3% of graduates with goals and a definite plan earned ten times as much as the other 97% combined.

Warning: The following paragraphs are just me spitballing. I do not have the answers.

Why do people who write their plans down seem to achieve so much success? Writing is an extended form of thought. When we transfer our thoughts into words on a page or screen, we are in some sense placing our ideas into the real world. I think that it is easier to conceptualize and iterate on ideas when we have them laid out before us. I also believe that there is something also to be said about the interplay between the activation of motor neurons, the emotion involved in an earnest acknowledgement of will, and those ideas that quite literally possess us being brought to life.

Plans provide a general foundation that we can orient the rest of our aims around. Once complex tasks are broken down into more achievable sub-goals we can incrementally achieve. If there is one goal we want to accomplish but do not manage to, we are at 0% completion which is pretty depressing all things considered. If we break that goal down into steps we may end up at 40% instead. That’s better.

Walking the Line Between Chaos and Order

A synonym for a goal is an aim. Thus, a person without a goal is figuratively, and perhaps literally, aimless. If there is no goal, no aim to judge our progress in the context of, our brains interpret this phenomenon just as if we were not moving towards a goal at all. No Dopamine is released and we experience an innately Nihilistic brand of negative emotion that seems to be all-encompassing for an alarming number of present-day individuals. In such a state of aimlessness, and possibly in the clutches of a major depressive episode, we are at dire risk of developing negative self-reinforcing routines through attempts to feel now-missing positive emotion by continually gratifying impulsive desires. Goals are necessary to prevent the emotional descent into anxiety, depression, and the associated Nihilism.Being forced to observe goal-less me meandering around the house is anything but entertaining, let alone remotely enjoyable. As the sun slips past the horizon of that Sunday’s evening, remembering the idealistically perfect weekend I had envisioned is even less enjoyable. As my head hits the pillow, the demarcation illustrated by the contrast between my desires and actions highlights a relative schizophrenia that both amazes and mortifies me. It’s amazing because I know that the clock is always ticking, and I can’t forget that. It’s mortifying because I know that the clock is always ticking, and I can’t forget that.

Just as bad as having no plan is its inverse extreme: having too much of a plan. There was a point in my life in which every aspect of the day had been planned out down to 15-minute intervals. This led to high levels of anxiety as everything took too long and I could never measure up to what had been planned. When plans become too granular, they are rigid and unable to conform to the changing circumstances of the problems they were formed to contend with. When the scope of a plan is too great and the allocable resources are too few as a result, there are too many variables to focus on and the plan falls apart. One can say that too much order is just as bad as there being too much chaos. On a fundamental level, there must be balance between these two aspects of reality.

The Consequences of Getting it Right

If you eat poorly, don’t drink enough water, don’t sleep enough, don’t exercise enough, or don’t properly manage your workload, your body and mind suffers. The consequences of ignoring these needs begins with mild annoyance underlying your personality, a decrease in performance and general well-being, and ends with utter contempt for being itself. On the flip-side, effectively managing your needs holds the potential to spiral you upwards just as quickly as things can go sideways. Imagine being 10% better or 10% worse; that’s a 20% spread between performing better or worse, and the effect compounds over time. If you became just 0.5% better every day for 365 days, you would be 517.47% better compared to when you began. Focus is key because everything you do or don’t do, small or large, matters.

Focus, extracting priorities from the infinitum of things that could be done and constraining one’s actions in the service of the selected goal respectively develops and implements a framework with which to deal with the challenges of life. Over time, a superstructure is amalgamated from the previous frameworks and takes form as a general mode of being for dealing with obstacles. As you encounter a wider gamut of and more difficult challenges, you become generally better at dealing with the spectrum of potential challenges. In this way, success is an iterative process.

The philosopher Mathers III asks “If you had one shot, or one opportunity to seize everything you ever wanted, in one moment, would you capture it, or just let it slip?” That one moment is every single moment of your life although some events are seemingly more impactful than others. Find something that captivates you, something that you dream about. Make doing that your overarching goal and generate a plan to achieve it. The fidelity does not matter to start, only that the plan is there. When is the best time to start? Now.

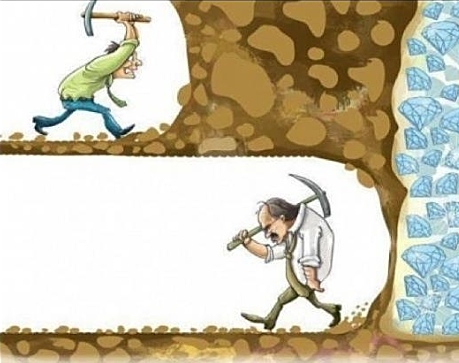

Excavate the world in search of what you’re looking for. Now that you have a goal, you roughly know where you’re trying to go. As you progress, you may encounter obstacles or hazards that must be bored through or moved around. At fairly regular intervals, you will have to stop, take a survey of how and where you are, and adjust your course based on that. Eventually you may, and most likely will, encounter issues that will cause you to need to retract yourself and fix what is in need of repair so that you can get back to progressing. The more time you spend working at this, the better you will get at avoiding issues and advancing with less effort. Eventually you will burst through your final barriers into a well of opportunity and find what you’re looking for in the process.

Metaphorically, life can be compared to drilling a well.